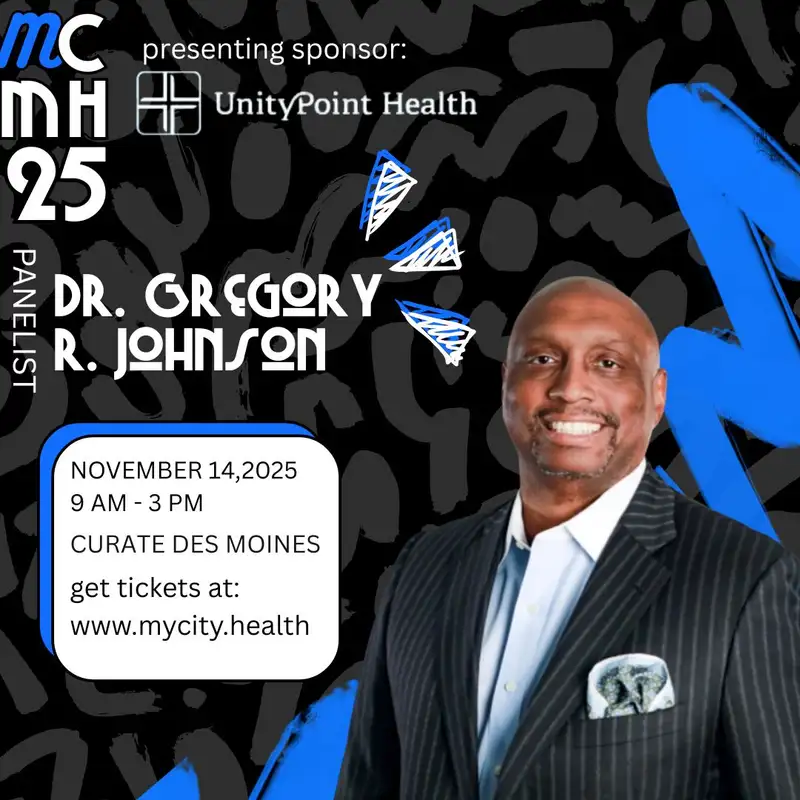

Black Men’s Health, Prevention & Equity in Iowa w/ Dr. Gregory Johnson

Corey Dion Lewis (00:01.309)

. Thank you for listening to My City Talks. This is the podcast powered by My City My Health and the My City My Health Conference. Today I have a great and exciting guest with me.

I am ready when you are.

Corey Dion Lewis (00:29.706)

If you have heard the conversation we had already before, then you would be just as excited as I am. have Dr. Gregory Johnson here today. Dr. Johnson, thank you so much for being on the podcast and being a speaker at this year's My City, My Health.

Thank you for the invitation. I'm excited to do this and I'm excited to be a panelist.

Yeah, so you know before we get into because you're on the the black men's health panel. Yeah. And you know have some definitely have some questions about that for you but I want people to know a little bit about you. You know your past and what got you to to the mooring.

Yeah, so it's a great question. This is the beginning of year two for me in Des Moines. I came from Houston, Texas, where I previously was the chief executive officer and chief health equity and diversity officer for a national multi-specialty medical group focused on the hospital space. And if people want to know my background and everything else, I'll give the short version, which is that I'm a

originally from Austin, It was raised there. I'm a doctor's kid. Most people automatically go, well, means that you knew you were going to be a doctor. It looked like he worked really hard.

Corey Dion Lewis (01:41.657)

actually.

don't see him that much. so I was like, how did this look? You know, let's figure it out. late in my college career, I went and I was just like, I don't really know what I'm going to do yet. And I spent some time at the VA hospital in Houston, saw a patient with, a terrible, terrible wound. had a spinal cord patient. He had a terrible infection that had really caused a giant ulcer in his back. It was one of the most horrific things you could see. And I remember turning to

to the physician at the time as a pre-med student, really not even a pre-med student, just somebody who was thinking about it. And I was like, that doesn't look like he's gonna live. And he said, no, no, no. If he didn't come here, he wouldn't. But here are the things we're gonna do to be able to help him. And here's your process. And it was six weeks of digging into what is dead tissue and just helping to clean the wound. But I watched over the course of that six weeks, not only the wound healed, but his relationship.

with his family healed with the relationship with how the entire care team was there to lift him up. And by the end of the six weeks, I was like, well, if this is what medicine is, I got to do this. Went to medical school in Houston and then residency. did a dual residency in both internal medicine and family medicine at the Osherner Clinic in New Orleans. And then went into private practice, did all that good stuff. But then I very quickly identified that

Unsurprisingly, there are financial incentives that are completely opposite in medicine that are completely opposite from what we need to do for patients. And I kept sitting there going, something's not right. Maybe I don't know anything. I don't know enough. So I spent some time in business school and was like, okay, well let me dig in and figure out because people say follow the money.

Corey Dion Lewis (03:36.482)

Right, my.

and tried to figure it out. Eventually got into balancing both administrative and clinical leadership and then kept advancing there because I kept saying, well, I've taken care of excellent job of 25 patients a day at the bedside. Well, and then I became a medical director. Okay, now I'm taking care of a couple hundred. Now I became a regional medical director in thousands. And I was like, how do you take what you think health care should be to populations of patients? So they call it population health. This was before it became a catchphrase. And I was like,

I want to heal. I'm a healer.

Right.

heal people and populations. And eventually got an administrative medicine and 15 years with my prior group, things were going well, kids were happy, everything else. But I wanted to be closer to a community because my group was always contracted through hospitals and I wanted to get a little closer. And so ultimately I started looking for jobs, happened to get a phone call saying, have you considered Iowa, Des Moines? And I was like, I've been there.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (04:41.392)

I hadn't been to Des Moines, I'd been to Cedar Rapids, I'd been actually to Mason City. I've been to Des Moines and I said, you know.

Okay.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (04:49.646)

If I'm being true to myself, this is one of the biggest opportunities because to get in and do exactly what I believe I'm been put here on this earth to do, which is to help improve people's lives through health care and recognize that UnityPoint Health currently, and we're working on expanding it, but currently touches, has 8 million plus patient visits a year. It's 8 million people's lives that you can have influence on. meeting Scott Kise,

and the leadership team at UnityPoint Health, I was convinced that UnityPoint has all of the components to be a transformative healthcare organization. So I signed up and so far.

So good. Yeah. So that's, that's awesome. So how does it feel going? You you had this, it sounds like you have this, population health mindset of, want to help more people with, with one solution or it's not one solution, but like it's one thing when you have, you have one-on-one with the patient. It's another where you're one on a thousand.

Well, it's see that the great part about going from bedside practice to an administrative role is that you're everything that you do at the bedside should inform where you're taking things from leadership perspective because every patient that I've ever encountered every physician I've encountered every advanced practice every nurse that I've encountered has influenced how We take that because at the end of the day I can say yeah, well we have this fantastic system We've got a balance than the

of the one, needs of the many, and understand that for any physician nurse, nurse practitioner, they're only focused on the one. The system has to be able to support what they're doing there. So yeah, that's my mindset, but it's a population health mindset with a bedside perspective.

Corey Dion Lewis (06:38.158)

Right.

Corey Dion Lewis (06:47.104)

Yeah, no, I love that. know, one of the things I found kind of like a fun challenge, but still challenging nonetheless, is when you're thinking about population health, right? Like, let's just take a diabetic population or that, you know what I mean? And you're like, okay, let's do A, but also those people in that group, there's probably thousands, there's probably, let's just take 10 people, all have different issues.

Right? So sometimes that one solution may not fit everybody. And you have to try to figure out, okay, how can I fit this piece into this hole that doesn't fit for other patients?

you were completely correct, means that we can't solve all the problems. What we can do is solve for whatever the macro problem is. So as an example, one of my biggest responsibilities at UnityPoint is helping to redefine what we call service lines. Service lines are really just a condition. For us, the big ones are cancer and heart care, right? Well, every patient comes in, whether you have a heart attack, a heart failure,

whether they have colon cancer, cancer, everybody's coming in with something different. But what can the system do at a population health to solve for that? Well, okay, go back to what I said, which is what do patients want first? If I'm sick, I need to see somebody. I need access. When we say the word access, people love to make it this nebulous concept.

access.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (08:25.25)

I and we, team, have really defined it as, no, if you have cancer or you have a heart condition, access is speed to treatment. Can you tell me how quickly you're gonna help me with my problem?

Speed to treatment. Yeah.

And then the second is, and then can this not be a miserable experience? Those are the only two things that as a system I can solve for. And so what do we have to do? Well, there are thousands of things that go on behind the scenes. But from the patient's perspective, it's what have you done to give me my speed to treatment and made sure that this, forget the...

Mm-hmm.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (09:10.936)

complete negative of I don't want this to be a miserable experience. In fact, can this be a great experience where I'm like, you know what, not only was this not bad, I actually feel better about the team that's treating me and the system that's treating me. And I know we're getting into it for the Black Beds Health panel, but I'm comfortable telling people, no, it's okay to go to the doctor. It's not a bad experience. We need you.

to go and get seen earlier because as you and I were talking before, I am a hospital medicine doctor. My entire practice when people come to me I say, Dr. Johnson I want to see you. You never wanted to see me coming because the only time I was going to see you is when you're in the emergency department and I'm about to admit you to the hospital. It's a place most people want to be. I don't want our patients in our health system, in our hospitals, unless you need to be there. am so sorry.

Right.

Corey Dion Lewis (10:08.27)

Right. Some important happen on ESPN. got to know.

We've got to get you. If you need to come to our hospital, we are more than capable of taking care of you, but we have thousands of clinics. I'd much rather that you get your care there.

Yeah. So true. think the mentality. there are a few things I want to bring up there because one, the first one, let's start with my first question is when it comes to black men's health, we ain't going. I'll make sure I have the links to some of these, some of the research in the description of like the numbers of black men that don't even have a primary care provider, but we're just not going.

for a multiple, multiple reasons, like I can't, we'd be here all day.

Yes, there are historic reasons, there personal reasons, there are any number of-

Corey Dion Lewis (11:05.94)

There are any number of reasons, but what is that? Like you said, we wait and wait and wait. I'll know I don't need it. I've heard, I feel good. Yeah. Right. Next thing you know, they're seeing you. Yeah.

Well, I would actually tell people, and I would say it jokingly, when I was seeing patients consistently of...

The minute that I was in the emergency department, was like, doc, I've never had to see the doctor. I would immediately go, no, this is going to be something pretty close to catastrophic because that time period usually means that, you know, anecdotal, but well, you'll have something serious wrong because it's gone without. you look at historically, there are any number of things, Tuskegee, syphilis, study, anything that's documents health disparity of the number of reasons why so many black people

historically said doctors don't they they treat us poorly and we get poor outcomes that are going to do bad things to us. There's a ton of history to reinforce that and you can look for it for the past 80 years. It's been well documented sad but well done.

Right, yep.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (12:14.722)

They're personal reasons. I've done, I've been in every single market from our market, Sioux City West to both the Buick and the Quad Cities in the East. Everybody has said the same thing to me, which is, Hey, even if I want to go transportation, isn't no joke. I can't get there. Yep. And typical healthcare access is at a bad time.

and they're not enough people and they're only giving me one appointment. I can't make it. have, I have a job to do and I got to put food on the family for me and for me in mine. There are any sorts of reasons why people don't do this and don't seek primary care. we don't make it easy right now. Part of my job as a chief medical officer for the system is to work in partnership with our physicians and our structure to say, how do we structure,

change so that way when I say speed to treatment first treatment should be screening first treatment I'm gonna look in the camera and say your first treatment should be screening for prostate cancer your first treatment should be screening for a colon cancer your first treatment

Mm-hmm.

Hehehehe

Dr. Gregory Johnson (13:39.032)

for heart disease should be getting your blood pressure and your cholesterol checked. But we don't think about it that way because it's, we all say the same thing, I say it too. I'm gonna change my diet. I eat terrible.

Yeah

Corey Dion Lewis (13:53.934)

I'll go next time. I'm gonna need...

This cheeseburger, I this is last cheeseburger I'm gonna be all right. We tend to avoid those things, but if we're thinking of how do we get upstream and how do we help ourselves to avoid the catastrophic, to reduce, you were, again, we're gonna talk about it at the panel, but in this state, the state of Iowa.

According to the Iowa Cancer Registry, black men have a 25 % increased likelihood of prostate cancer.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (14:31.47)

That's a big no-

Yeah. And if you're not being for worst fall with, with the innovation in that space, um, even more treatable, right? But like, if you're not doing the things, you're not doing the screenings and catching it. Look, I think black men can get 40 years old, you know, at 40. Right? Like if you're not doing that and you're waiting, there's always, you know, there's always too late.

consequences to waiting which is why unfortunately so whether I brought we brought up cancer and cancer screenings you can get blood tests to be able to do this now the colon cancer screening tests don't even include you can get a colonoscopy but we can do a test that you can do at home of stool kits to help

Yep, Kola-Gargs, it's okay.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (15:22.814)

Take some of that, this is invasive, out of it and into we can do this. Yeah, nobody likes getting their blood taken, but getting your cholesterol, getting your blood pressure checked, these are all things that actually help to stave off very serious disease with serious consequences and, you know, whatever we can do as a health system, but also what we can ask people to do individually to get back into those primary care offices.

Yet 100%. I want to talk about this specifically from a systems perspective.

You said something before we started recording. There's something that I deal with a lot as a prevention person, holistic healthcare and all that jazz, where I'm more looking at the value of the investment instead of the return of the investment. And sometimes it's hard to articulate, hey, me helping this person reduce their A1C by two or three, four points means X amount of money.

But in the mind it's like, what? That's not money in my pocket. Exactly. Yeah. But you were telling me, can you break down the cost of an unhealthy community and what that does for the state?

Where's that money going?

Dr. Gregory Johnson (16:41.038)

Yeah, so I'll, I'll, I'll start it. I'll try and break it down relatively quickly in terms of a couple levels. So when I say things like health disparities, it means that people have different outcomes based on where you live, what you look. Um, and I keep it very simple that health equity means that you have the opportunity for the same outcome, which I think most people who engage in our health system want the same opportunity.

Yep.

Corey Dion Lewis (17:10.445)

100%. health. Yeah. Or why would you be in healthcare?

Well, would, right, look, just because of where I live, I still want to have access to the same.

100%.

There are lot of conversations that are ongoing about health equity and health inequity and whether or not that needs to be addressed. And for me, I want to speak people's language no matter what's going on. Some people say it's a moral imperative. That's one argument. Some people say it is a people imperative, meaning that when we're dealing with this, as a health care organization or institution, you attract more people. That's another thing to the side.

math because it's super objective and the state of Massachusetts as well as Tulane University both Tulane in 2018 and University of sorry and the state of Massachusetts I think it's 2023 both did studies on well okay we know that there are health inequities in our system how much does this cost us state of Massachusetts calculated out it's 5.3 billion with a B per year

Dr. Gregory Johnson (18:23.914)

for patients of color who are having unnecessary hospitalizations, increased mortality, death. 5.3B with a billion. Man. Factor that now one state, OK, well, that's Massachusetts.

What does that mean for Iowa? Taking the same logic and everything else, and this is my math, so it could be wrong a little bit, but I think it's directionally correct. The state of Iowa, number's probably 8.6 billion with a B dollars. Now people are like, well, you're right, it's not my money. Well, actually it's your tax dollars and it's the infrastructure that goes in to be able to care for all of those. Imagine if we redirected

you

Dr. Gregory Johnson (19:13.098)

And for Iowa, is rural inequities as well as racial inequities. So if we were spending time thinking about where we're putting our dollars, our dollars should be, for me, saying, you mean, tell me I can spend $8.6 billion less if we can eliminate health disparities in this state? Okay. That sounds like a good plan to me, but

Yeah.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (19:39.554)

That means that there's outreach into communities. It means it is figuring out how do you get to people that either can't access the transportation issue or what do we structurally have to do to be able to fix it. But that is money that can be reinvested in so many other things.

But to the point you have to reach the individual patient and we, both the state as well as systems like UnityPoint, have to say, okay, well how are we reconfiguring ourselves to meet the needs and help to reduce cost and get better outcomes? And the better outcomes are fewer people dying from preventable disease, period.

Period. you know, something that you hear a lot, or least I hear a lot, and I have said a lot, is trying to meet people where they are at, but like that is easier said than done. Absolutely. You know what mean? That's not something that, like, yeah, gotta meet people where they're at. Okay.

There has to be a whole plan to do that. I think it's important because to your point, like transportation is a huge problem. Even for somebody that you would think in Des Moines, which is not as, it's not Houston. You know what I mean? But like you would think, you would think that people would have easy access to get to places, but not everybody has that same.

privilege, right? Like I can get somewhere anywhere I want to within 15, 20 minutes. If it takes 30 minutes, I got a problem. But for somebody who's maybe 10 minutes away from a UnityPoint clinic or somewhere or 15, they can't make it. And then taking into account, this is something that I don't think we talk a whole lot about when it comes to transportation is

Corey Dion Lewis (21:26.944)

I've seen patients who have transportation through their insurance. They have an appointment at 11 o'clock. drops them off at eight. So they're hours early. Then they're done with their 20 minute appointment by 11, 25 or whatever. Now they're waiting for transportation for another three hours. Do you think that person's going to want to come back for an appointment?

No, you're right. mean, appointments can take forever because we don't have perfect transportation. Yeah. Or and forget perfect. We don't even have adequate transportation to be able to get people there and respecting that how they're going to be able to do that. And to your point, right, we don't have a public transportation. We have public transportation here in Des Moines. But again, if I spread out throughout the state, I'm at Fort Dodge. We have patients that if you're

minutes away from Fort Dodge, you're in many times you're in a very rural community. If you don't have a vehicle, what does that mean? Yeah. How do we get you to get your screening? Because it's not that you don't want to go, is you can't get there. And God forbid now you're waiting until it's a crisis that you can call the ambulance.

that you hope is there to be able to come and get you. And so, yeah, I don't know that there's a perfect solution, but I think that part of the reason why as a system we track the social determinants of health for both our inpatients and outpatients is it's not because, it's checking a box. It's because we're trying to understand at a population level.

how bad is the problem and then how are we going to engage in saying to your point, I can't solve everybody's problem. But if I can solve 10 % of the problem, we've made a difference. And maybe that 10 % sparks the next idea of the next, and we're doing things like gas cards and other things to try and help patients get in and out of our hospitals and our clinics to be able to do that. But we're trying to be thoughtful in terms of that approach, but you're right, it's a massive.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (23:41.356)

problem and it's a huge opportunity for us to engage with community partners as well as governmental institutions to try and solve that

You know, I love that. want to bring it back to the panel, the Black Men's Health panel a little bit. What is, is there something that you're hoping that our audience maybe comes, goes away with when we're talking about Black Men's Health, specifically here in Iowa?

Yeah, for me, think that, I mean, always the takeaway is your physician or your nurse practitioner is your partner in helping to solve these problems. that where many of us are uncomfortable, nobody likes the word vulnerable. Nobody. As much as it's become a word of

Right.

You should feel comfortable with nobody like you. The vulnerability in terms of sharing with your physician and his or her team about, here are my barriers to getting in here. And sometimes that's a phone call. And sometimes if you have a computer and you access MyChart, it's a MyChart message. And sometimes it is when you're sitting in the office. But the most important thing is you're...

Dr. Gregory Johnson (25:08.056)

For me, it's a change in perspective of your doctor interaction as a transaction. And it's the mindset of your doctor is your partner in your health. And if one of your challenges in accessing health is, can't get here.

Mm-hmm.

I'm willing to make a bet, yes I sit in UnityPoint Health, but this is for anybody that's listening and I look to the camera just to say that. Your doctor, your nurse practitioner, your nurse is a partner in your health.

And that engaging them in terms of the vulnerability of saying, here's where I need help. We may not be able to know to fix it, but I guarantee you that we will factor it in to figuring out how do we continue to help you in your journey. And for me, yeah, I have all the stats. I can tell you where things are going. I can tell you the outcomes. I've learned this for my new home state. have learned, and not just the state, but the states of

Illinois and Wisconsin too. I'm very much focused on what we're doing and knowing the stats. But at the end of the day for the individuals, it's we're designing certainly our system as we're your partners in health and that you need to engage because waiting.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (26:31.822)

just leads to the same results. And right now the same results for black men are 25 % greater likelihood of diagnosis and potential mortality from a curable cancer, prostate cancer. Same thing for not quite the same percentages for colon cancer. These are things that are preventable disease. And that's the part I keep saying, everybody's like, oh, everybody has a heart attack. Everybody shouldn't have a heart attack.

That is not a normal thing in life.

You mentioned diabetes and a partner in health and I tell people people because so many people have diabetes they've normalized. Yep. And they've just well you know I got sugar. You know. Diabetes is the second leading cause of heart attacks blindness stroke.

you grew up with it being normal.

Corey Dion Lewis (27:22.296)

Mm-hmm.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (27:27.118)

Getting right now the American Diabetes Association estimates that there are today 100,000 undiagnosed Iowans.

Mmm.

with diabetes, meaning the second highest cause of cardiovascular disease, including stroke, 100,000 people are walking around and have no idea. Engage your...

I have no idea. Yeah. Doctor. Yes. That blurry vision ain't normal.

That is not normal. well, you know, was walking up the stairs and my chest, you know, but I'm okay. get to the, it's not. Age your physicians, engage your nurse practitioners, engage your wherever you can because at the getting into the front door and acknowledging that, yeah, I feel risky. I feel vulnerable because I'm coming. I'm getting in here.

Corey Dion Lewis (28:09.721)

It's not normal.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (28:29.25)

We acknowledge as a health system, any health system, UnityPoint included, we haven't done the best job yet, but there are people, most of us, that are really focused on how do we get things better and how do we help you in your situation, but that requires you to engage.

Yeah, yeah. And there's only so much you can change with that experience. Like just saying hospital for some people is anxiety. yeah. So like there's some, there's some innovating that can be done for sure. But sometimes you gotta do things scared too, you know.

I get it.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (29:06.846)

No, you bring it up. Everybody's scared about different things. So we started a couple months ago a telemedicine outreach clinic for cardiology in Fort Dodge.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (29:22.368)

We were just like, we to get specialty care in Iowa is a challenge to get it in more the more rural areas of the state. Super difficult. We were just like, we have a need. And at first, there were people like, this doctor's not here. Like you've got me talking to you. What are you doing? What is but interestingly enough, the patient experience was, wow, it.

Yeah.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (29:51.394)

First of all, the doctor was completely engaged in the discussion. There was a nurse here that was walking through everything and then I'm now engaged in the system and I'm getting treatment where I couldn't get it before or we didn't have access to a specialist. Now I know where I sit, patients are now getting, yeah, they're getting heart surgeries when they typically wouldn't survive long enough to get it, but now they're getting in and getting the procedures they need

they're involved in our clinic. And so you talk about access and figuring this out and vulnerability. Sometimes it is innovation like telemedicine. Sometimes it is understanding that yeah, there's gonna be a van that comes up here and I don't wanna go to a van. The van is your access. And let, and understand that.

Yeah.

Corey Dion Lewis (30:39.566)

Yeah.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (30:46.033)

We want to listen and we've got a project going on now and I'll hopefully get a chance to come back and talk to you about it. But we're spending dedicated time in the county to sit down and create community scientists to tell us we've identified this problem. We don't know. I'm not coming in here to tell you how we want to treat you. You tell us how to best engage. That's the way that a health system engages with the community to say,

We're not here to say, we're better than you and we know best what's for you. You tell us and we'll collaborate and come up with the best solution. And yeah, everybody would want the best heart surgeon to be right next door. It's not the way it works. But if we figure out how to provide that care through innovation, through technology, through utilizing.

Yup.

the whole phone that almost everybody has. Now we've figured out how to allow people to engage on their, you know, it's not perfectly on their own schedule, but we're working to figure these things

things out. No, that's good. No, I love that. You know, Dr. Johnson, thank you so much for being here, for being on the panel. This be your first, I think it's your first My City My Health experience. don't know what you've heard about My City My Health, but it just, I'm excited for you to experience it.

Dr. Gregory Johnson (32:09.526)

I'm looking forward to it. I was told bring my A-game so I'm gonna be ready.

Yes, for anybody that's listening or even watching on YouTube that wants to learn more about you, learn more about what we're doing at, what you're doing at UnityPoint, where can they find you, where can they connect?

Best way to connect for our system is www.unitypoint.org. It's the way that you can get a whole bunch of information. It's populated with a ton of information, not just about specific conditions. We didn't even get to talk about immunizations for pediatrics and all that I'm passionate about. But it also connects you with our clinical team members. You can access and get in schedule appointments. When I tell you engage with your physician,

that's exactly what I'm asking people to do, which is you may think you're the healthiest in the world. I've spent a ton of time in the gym, but my blood pressure still has to be treated. These are things that we have to do to help prevent catastrophic disease and keep people out of the hospitals and home with their families. So check out www.unitypoint.org and check out our health system.

Awesome. Awesome. Again, thank you so much. Everybody that's listening, if you liked this conversation, I want to see you November 14th at Curate Des Moines for My City, My Health Des Moines. It is always a good time. It is a safe space for a community and for conversations. Go over to mycity.com.

Corey Dion Lewis (33:43.114)

mycity.health, almost forgot my own website, mycity.health. You can register there, you can see the agenda and who all the other panelists are. So again, thank you so much for listening to My City Talks powered by My City My Health. I'll talk to you next time.

Take care.